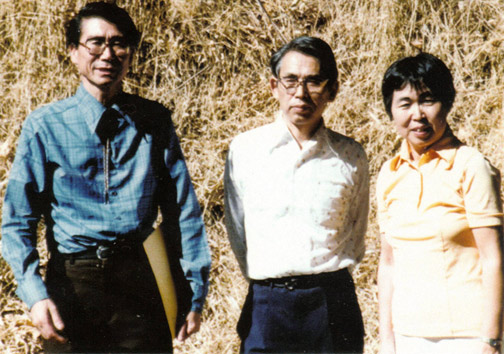

Kiyoko & Kiyoshi Tokutomi

by Patricia J. Machmiller and Yukiko Tokutomi Northon

|

|

Kiyoko Shibata Tokutomi was born 28 December 1929 in southern Japan in a small farming community called Nabeshima in the prefecture of Saga near Shimabara Bay and located about fifty miles from Nagasaki. She was the second child of seven born into a family that made their living raising rice. She attended Saga Girls’ High School from which she graduated in the spring of 1945. She immediately enrolled in Saga Teachers’ College.

Kiyoko Shibata Tokutomi was born 28 December 1929 in southern Japan in a small farming community called Nabeshima in the prefecture of Saga near Shimabara Bay and located about fifty miles from Nagasaki. She was the second child of seven born into a family that made their living raising rice. She attended Saga Girls’ High School from which she graduated in the spring of 1945. She immediately enrolled in Saga Teachers’ College.

In the summer of 1945, her parents, heeding the warnings in leaflets dropped by American pilots over Saga, bundled all their children in their winter jackets and sweaters and took them to hide in caves in the mountains near their town. And so it was the whole family, except for one uncle who tried to watch, survived the atomic cataclysm of Nagasaki.

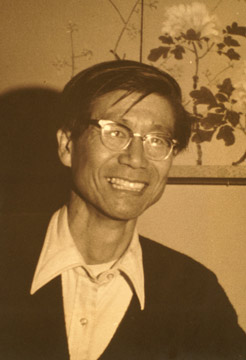

In 1948 she graduated from college having majored in Japanese literature with an emphasis in haiku and took a position at Nabeshima High School where she taught literature and dance. It was here that she met Kiyoshi Tokutomi, who was teaching English there. At age nine Kiyoshi, born in the United States, had been sent by his mother along with his two siblings, a brother and a sister, to Japan for schooling after his father had died. When the war broke out, he was trapped there unable to contact his family in the United States.

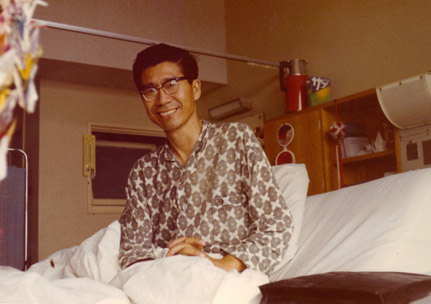

It was a time of terrible struggle for food; Kiyoshi had been sharing whatever food he acquired with his students often going without himself. Kiyoko admonished him, “You are not the Buddha; you have to eat.” It was at this time that he contracted tuberculosis. Even though he was extremely ill, no medical help was available in Japan and his return to the United States required that he prove that he had not been a traitor to the the country. So while his mother pursued his case in the courts, his health deteriorated. All that saved him was the streptomycin she was able to send him from the America. Finally, in 1951 he was given permission to return to the United States where he was promptly hospitalized.

It was a time of terrible struggle for food; Kiyoshi had been sharing whatever food he acquired with his students often going without himself. Kiyoko admonished him, “You are not the Buddha; you have to eat.” It was at this time that he contracted tuberculosis. Even though he was extremely ill, no medical help was available in Japan and his return to the United States required that he prove that he had not been a traitor to the the country. So while his mother pursued his case in the courts, his health deteriorated. All that saved him was the streptomycin she was able to send him from the America. Finally, in 1951 he was given permission to return to the United States where he was promptly hospitalized.

He invited Kiyoko to come to America and she came in 1954. His long hospitalization had not improved his condition so it was decided to surgically remove one of his lungs. She was there for the first surgery and a second surgery to fix the first and a long succession of hospitalizations thereafter. For the remainder of his life, he would have to have his lung irrigated daily, a ministration that she would perform. She spent her days at San Jose City College studying English and the rest of the time at his bedside. By her own account, her first year in the United States she could neither speak nor comprehend what was being said. During her second year, she could understand everything but could not converse. She began to speak English in the third year.

They were married in 1957 and that year they had one child, a daughter, Yukiko. Because Kiyoshi was not strong enough to work, Kiyoko took a job at Fairchild Semiconductor on the assembly line. Her work was noticed because of her dexterity and precision; as a result she was often asked to perform work for engineers. The accuracy with which she kept records of the experiments and her ability to read and understand graphs and mathematical tabulations led to her transfer to the technical manuals department where she was tasked with laying out and proofreading engineering reports. The company discovered she had an eye for page layout and graphics and a well-developed sense of aesthetics. This attention to the smallest detail is reflected in her haiku.

They were married in 1957 and that year they had one child, a daughter, Yukiko. Because Kiyoshi was not strong enough to work, Kiyoko took a job at Fairchild Semiconductor on the assembly line. Her work was noticed because of her dexterity and precision; as a result she was often asked to perform work for engineers. The accuracy with which she kept records of the experiments and her ability to read and understand graphs and mathematical tabulations led to her transfer to the technical manuals department where she was tasked with laying out and proofreading engineering reports. The company discovered she had an eye for page layout and graphics and a well-developed sense of aesthetics. This attention to the smallest detail is reflected in her haiku.

In1962 because Kiyoshi was still suffering from tuberculosis in the remaining lung, it was decided to try a new medication, kanamycin, developed in Japan. One of the side effects of the medication, however, was complete loss of hearing, and this happened to Kiyoshi.

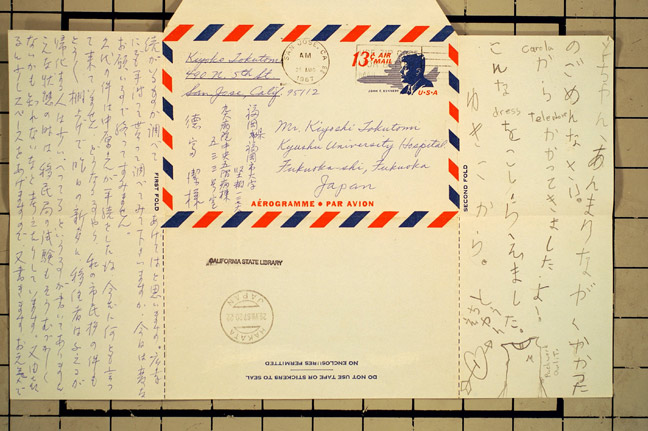

One of the amazing things about Kiyoshi and Kiyoko was their ability to overcome adversity. This time of trial is documented in the letters they exchanged in 1967 when they underwent a five-month separation during the time Kiyoshi spent in Kyushu University Hospital in Japan in an attempt to cure his hearing loss.

These letters have been translated and published in Autumn Loneliness: The Letters of Kiyoshi and Kiyoko Tokutomi, July–December, 1967 (Walnut Creek, California: Hardscratch Press, 2009). The letters show how they both emphasized the positive and always looked forward. After they determined that Kiyoshi would never recover his hearing, Kiyoko decided that she would introduce him to her passion, haiku. Her idea was that he could participate without hearing and be able to interact with people socially at literary gatherings, where much of the discussion was written language. Thus began her extensive years of writing both Japanese and English haiku. Kiyoko, together with Kiyoshi, founded the Yuki Teikei Haiku Society in 1975. This is the same year that they joined Kari, the Japanese haiku group of Shugyo Takaha. In their teaching to English-speaking writers, they focused on the essence of the kigo, the traditional haiku form, and the importance of simplicity.

The Tokutomis with Kazuo Sato (international director of Tokyo’s Museum of Haiku Literature), at Yuki Teikei Haiku Society ginko, Vasona Park, Los Gatos, California, 8 September 1979.

In 1979, Kiyoko led a group of haiku poets to the Fourth International Poetry Conference in Seoul, Korea, and then on a tour of Japan. While in Korea she met many Koreans whose anger toward the Japanese was still fresh; the people who accompanied her were astonished by the ferocity of it. They were also impressed with her and the way she dealt with this anger quietly, firmly apologizing for herself and for her homeland with no equivocation. The trip to Japan would become one of many.

Kiyoshi died in 1987; in spite of her grief, Kiyoko continued on with the work they had started together. In 1997 she was asked to speak at the Haiku International Conference in Tokyo about their accomplishment. She continued to write haiku in Japanese and English and in 1999 she was named dojin in Kari, a designation given to the most accomplished members. And in 2000 the Yuki Teikei Haiku Society celebrated its 25th anniversary. In September, 2001, she read at the celebration of the Fiftieth Anniversary of the United States–Japanese Peace Treaty held in the Bay Area.

Kiyoko had three grandchildren, whom she adored. She actually “composed” their Japanese names by asking what traits their parents wished for them. Using this information and their birth dates, she wrote the calligraphy for their names in a specific way to convey the special meaning. For many years, she taught calligraphy and the Japanese language at the Japanese Language School in San Jose.

In 1995, after she retired from National Semiconductor (Fairchild had been purchased by National), Kiyoko moved to Ben Lomond in the Santa Cruz mountains, a town that she fell in love with. She had always wanted to live with lots of green and water nearby, and now she had both. The influence of the Ben Lomond landscape, redwoods, and the nearby creek seen through her windows can be felt in the haiku she wrote in 1995 and after.

In August 2000, Kiyoko was diagnosed with cancer and days later with Alzheimer’s disease. In November 2002, she traveled to Japan and visited her hometown and all of her siblings, childhood friends, and their families. This would be her final trip to Japan. A diary of this journey written by Yukiko is available at http://www.konaaina.com/japan/index.html.

Her book of haiku, Kiyoko’s Sky: The Haiku of Kiyoko Tokutomi, translated from the Japanese by Patricia J. Machmiller and Fay Aoyagi, was published in December 2002 (Decatur, Illinois: Brooks Books). At the Yuki Teikei winter party when the book was presented to Kiyoko, she began to read aloud the Japanese version of the poems. Patricia, who had been her primary presentation partner for many years, quickly came and sat next to her and read the English versions, as they had done so many times before. This would be Kiyoko’s final presentation, a true gift given to those present. Among the members that very stormy evening were two guests, her daughter Yukiko and her eldest grand-daughter, Nicholette. Kiyoko died two weeks later on Christmas Day, 2002.

Note: The photographers of the photos presented in this essay are unknown except for the first photo of Kiyoko, which June Hopper Hymas took at a Noh-mask viewing in Kyoto, Japan, 1997. All photos are provided courtesy of Yukiko Tokutomi Northon except for three: 1. The first photo of Kiyoshi is a photo by June Hopper Hymas of the original photo in the American Haiku Archives at the California State Library. 2. The first photo of Kiyoko is courtesy of Patricia J. Machmiller. 3. The last photo with Professor Sato is courtesy of Patricia J. Machmiller.

Books by Kiyoko & Kiyoshi Tokutomi

Kiyoko’s Sky: The Haiku of Kiyoko Tokutomi. Patricia J. Machmiller and Fay Aoyagi, trans. Decatur, Illinois: Brooks Books, 2002.

Sixteen Autumn Haiku, Kiyoshi Tokutomi. Fay Aoyagi and Patricia J. Machmiller, trans. San Jose, California: Black Palm Press, 2005.

Autumn Loneliness: The Letters of Kiyoshi and Kiyoko Tokutomi, July–December, 1967. Tei Matushita Scott and Patricia J. Machmiller, trans. Walnut Creek, California: Hardscratch Press, 2009.

(Note: The original letters in Japanese are in the American Haiku Archives at the California State Library. The photo of the letter is by June Hopper Hymas.)

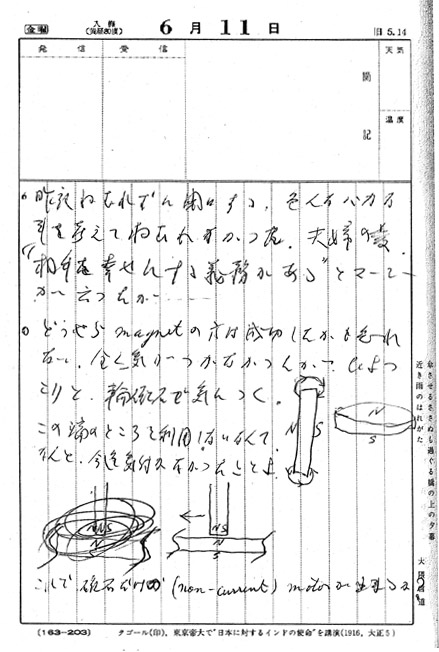

The Diary of Kiyoshi Tokutomi. Tei Matsushita Scott, trans., with introduction by Patricia J. Machmiller. Lulu (http://www.lulu.com), 2010.

(Note: Kiyoshi kept a diary from 1957 when his daughter was born until he died. The original diaries written in Kiyoshi’s hand in Japanese are in the American Haiku Archives at the California State Library.)

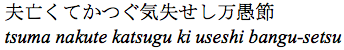

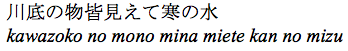

Selected Haiku by Kiyoshi Tokutomi

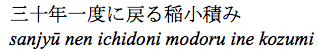

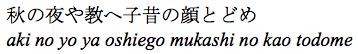

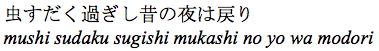

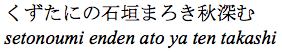

Kiyoshi Tokutomi composed the following haiku in Japanese while visiting Japan, 19 October to 8 November 1983. The original document is in the American Haiku Archives at the California State Library. They have been translated by Fay Aoyagi and Patricia J. Machmiller.

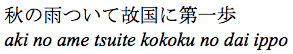

braving autumn rain

the first step into

my homeland

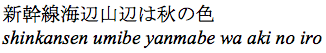

bullet train—

seaside, mountainside, both

in autumn colors

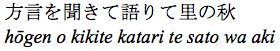

Listening to and

speaking my local dialect

autumn village

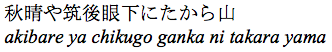

blue sky of autumn—

from Takara Mountain

Chikugo under my eyes

Chikugo: Ancient name for Fukuoka Prefecture in Kyushyu.

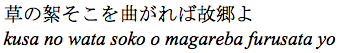

pampas grass plumelets

turning the corner there’s

my home town

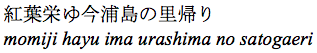

red leaves glow—

a modern Rip Van Winkle

returns home

Urashima: A character in a Japanese legend similar to Rip Van Winkle. After living in the Sea Dragon’s Castle under the ocean, he returns to his village as a very old man and no one remembers him.

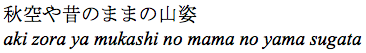

Autumn sky—

the shape of the mountain

as in the old time

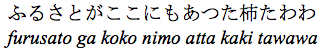

My hometown

I find here, too

ripe persimmons

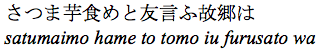

“Taste the sweet potatoes”

my old friend says—

home town visit

Thirty years

rushing back at once

rice plant chaff

Autumn night—

my students still have

the faces of long ago

Loud chorus of insects—

the night of old times

comes back to me now

Ancient salt fields

of the Inland Sea—

high autumn sky

![]()

Stone fences of Kuzutani

with the round edges

autumn deepens

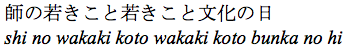

How young my master is

how very, very young!

Day of Culture

At a meeting with haiku master Shugyo Takaha on the fifth anniversary of Kari, celebrated on Bunka no Hi, a Japanese national holiday, November 3. Before WWII it was a somewhat religious, Emperor-related holiday.

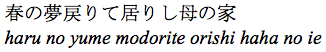

Autumn lights flickering

my homeland is already

under my eyes

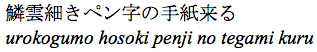

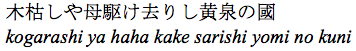

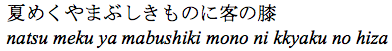

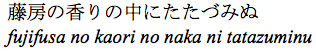

Selected Haiku by Kiyoko Tokutomi

These haiku translated by Patricia J. Machmiller and Fay Aoyagi are from Kiyoko’s Sky: The Haiku of Kiyoko Tokutomi (Decatur, Illinois, Brooks Books, 2002). The original haiku were first published in Japanese in Kari, the haiku publication of the Kari Haiku Society. These periodicals are in the American Haiku Archives at the California State Library.

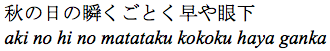

Spring dream—

I am back in

my mother’s home

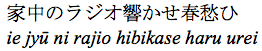

Filling the whole house

the blast of the radio—

spring melancholy

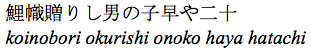

The carp banner

I gave to the little boy—

he’s twenty now

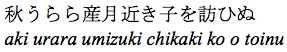

Bright day in autumn—

I visit my child

in her ninth month

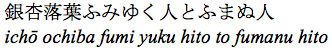

Gingko’s fallen leaves—

those who step on them

those who do not

![]()

End of autumn

what they call a grandchild

has been gifted to me

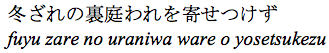

Winter bleakness—

I find I’m not invited

into my backyard

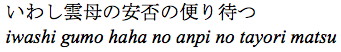

Sardine cloud: I wait

for a letter wondering

if my mother’s well . . .

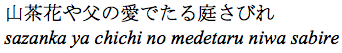

White camellia—

my father loved this garden

now so forlorn

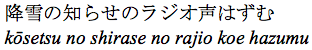

Snow starting to fall—

the announcer’s voice takes on

added excitement

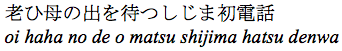

The silence before

I hear my old mother’s voice—

New Year’s phone call

A child does not know

of life’s melancholy—

the loquat blossom

That squirrel

stealing my birdseed—

a green-leafed wind

Crickets—

their competition

is exceptional tonight!

April Fools’ Day—

my husband who loved to play tricks on me

already gone

Mare’s tail clouds—

a letter arrives

in her frail hand

Withering blast!

Mother, you ran so fast to

that other country . . .

Lost—with my husband—

my wish to play jokes

April Fools’ Day

Such a summer day!

among the dazzling things

are my guest’s knees

At its bottom

all things are visible

winter river

![]()

Nobody visits

and here I am wishing to share this

crushed ice

Chemotherapy

in a comfortable chair

two hours of winter

(original in English)

Wisteria:

inside its fragrance

I pause